Making art is an expensive habit. If your family was rich to begin with, you’ll drain their resources in pursuit of that habit, with long odds of paying dividends in the end. If nothing else, your very existence will be a status symbol, a decoration and an advertisement of your family’s success—like having a son or daughter in the church once was. If you come from a middle-class or, God forbid, poor background, pursuing it will very possibly ruin your life, and make your professional endeavors a very awkward subject at holiday gatherings. In part at least, this is what Inside Llewyn Davis is about.

Joel and Ethan Coen have done as well for themselves as anyone at pursuing the habit. They do last-quarter-of-the-year prestige releases that the entire family can agree on seeing over the holidays, and at this point even your (presumably non-cinephile) family probably knows who Joel and Ethan Coen are. Along with the output of Alexander Payne (Nebraska) and Martin Scorsese (The Wolf of Wall Street), their work comprises something like a contemporary American Cinema of Quality.

Inside Llewyn Davis opens today in New York City, where it is mostly set. It’s a December release, but the movie feels like February. It feels like the day after a snowfall in New York, when the pristine white blanket of last night has turned into a sponge for car exhaust, the gray mid-day after, when yesterday’s snow, half-melted, transforms every curb into a slushy moat, and every crossing of the street becomes an Olympian long jump. It feels like the moment when you mis-time that jump, or don’t calculate for an unseen pothole, and land up to your ankle in frozen sludge, when you’re left standing there with soaking socks, too far from home to think about changing them, though maybe you wouldn’t even have a fresh change handy if you went home, and so you just walk around all day with your feet cold and wet, hating life and everyone around you with their goddam dry socks.

Llewyn Davis is a folk singer kicking around New York in the winter of 1961—or, more accurately, being kicked around it. He’s the product of a bridge-and-tunnel working class family, which means his choice of a “creative” life is an especially precarious, irresponsible endeavor, and as we learn, responsibility is not Davis’s strong suit. His father was a seaman, and Davis has shipped out with the Merchant Marine in the past for money. Davis plays music for money, too, but not much of it is coming in, and he’s contemplating going to sea again when we encounter him in the midst of career doldrums. Davis is played by Oscar Isaac, a Julliard-trained actor who can also sing, play guitar, and pull off a Brooklyn brogue, who here has far-and-away the highest profile part of his career. Isaac, and presumably Davis, is in his early 30s—that uncomfortable age where one feels especially young and promising with every success, and especially old and played out with every failure. With just a touch of iron in his black, curly hair and beard, dark circles under his eyes, and the beginnings of a paunch, he’s not a kid, exactly.

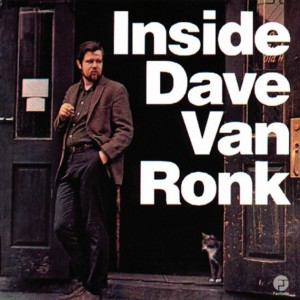

The Merchant Marines detail was taken from the life of Dave Van Ronk, whose posthumous 2005 memoir The Mayor of MacDougal Street the Coens mined for color, and whose 1963 album Inside Dave Van Ronk inspired the film’s title. The Coens cited the cover of another 1963 LP, The Freewheeling Bob Dylan—the iconic image of Dylan with then-girlfriend Suze Rotolo huddled against him, walking down a snowy Jones St., Dylan wearing a jacket far too thin for deep winter, as Davis does—as having been an influence on their film’s atmosphere and palette. Llewyn Davis was shot by Bruno Delbonnel, who treats each image with a milky diffuseness, and the film contains some of the whitest white people that I have ever seen, with Carey Mulligan practically translucent. (Mulligan gives the film’s worst performance, but at least she’s visually compelling.)

The Merchant Marines detail was taken from the life of Dave Van Ronk, whose posthumous 2005 memoir The Mayor of MacDougal Street the Coens mined for color, and whose 1963 album Inside Dave Van Ronk inspired the film’s title. The Coens cited the cover of another 1963 LP, The Freewheeling Bob Dylan—the iconic image of Dylan with then-girlfriend Suze Rotolo huddled against him, walking down a snowy Jones St., Dylan wearing a jacket far too thin for deep winter, as Davis does—as having been an influence on their film’s atmosphere and palette. Llewyn Davis was shot by Bruno Delbonnel, who treats each image with a milky diffuseness, and the film contains some of the whitest white people that I have ever seen, with Carey Mulligan practically translucent. (Mulligan gives the film’s worst performance, but at least she’s visually compelling.)

When we meet Davis he’s in the process of promoting his solo LP, Inside Llewyn Davis. Like just about everything else that Davis undertakes, this endeavor is doomed to failure. His life is fucked up, and he’s accountable for a fair portion of what’s gone wrong. He spends his nights crashing on increasingly scarce friendly couches, spreading bad luck as he does. “Everything you touch turns to shit, like King Midas’s idiot brothers” says his sometime-lover, Jean (Mulligan), who doesn’t want him around anymore because he may have knocked her up, unbeknownst to her live-in-lover and singing partner, Jim (Justin Timberlake). Davis was himself part of a not-particularly-successful duo, Timlin & Davis, and is now a not-at-all-successful solo act, playing basket shows at the Gaslight Café in the Village and haggling with his record label for nonexistent royalties. His former partner, Mike Timlin, glimpsed only on the sleeve of an LP alongside a clean-shaven and much younger-looking Davis, committed suicide sometime in the not-so-long-ago past by jumping off of the George Washington Bridge. Even this act is judged a failure by Roland Turner (John Goodman), the loquacious jazz musician who Davis shares a car ride to Chicago with: “Pardon me for saying so, but that’s pretty fucking stupid, isn’t it? George Washington Bridge? You throw yourself off the Brooklyn Bridge, traditionally. George Washington Bridge? Who does that?”

Davis is headed to Chicago in a last-ditch effort to salvage his career, auditioning for the manager of the Gate of Horn club, Bud Grossman. F. Murray Abraham plays Grossman, a thinly-fictionalized version of actual Gate of Horn manager and folk profiteer Albert Grossman. (The goatee he’s wearing, however, is purely Ahmet Ertegün.) When Davis finally corners Grossman, he plays him “The Death of Queen Jane,” an adaptation of a traditional English ballad describing the difficult labor and death of Henry VIII’s third wife, Jane Seymour, in 1537. After listening to Davis’s “Queen Jane,” Grossman gives his considered opinion. “I don’t see a lot of money here,” he says, to which Davis responds with the forbearing “Okay.” This “Okay” is something like Davis’s catchphrase, delivered several dozen times, conveying as many different shadings of surrender. (Grossman goes on to offer Davis a slot in a trio that he’s putting together, a fictionalized Peter, Paul, and Mary. One imagines the gig will go to Jim and Jean instead.)

The song isn’t merely a break in the action, but a continuation of and ironic commentary on the narrative. Unlike the ballad’s fretful King Henry, Davis has no aspirations to fatherhood. When arranging an abortion for Jean, he learns from the doctor that the last girl who he “got into trouble” almost three years ago didn’t go through with the procedure, and moved back home to Akron to have the kid instead. Later, driving back East to New York without so much as a gig for his trouble, Davis sees the lights of Akron pass in the distance, but doesn’t slow to stop. Davis even abandons the lone responsibility that he does take on—the care of a stray orange tabby cat that he adopts after mistaking it for the cat of one of his Upper West Side benefactors that had escaped through his negligence.

The song isn’t merely a break in the action, but a continuation of and ironic commentary on the narrative. Unlike the ballad’s fretful King Henry, Davis has no aspirations to fatherhood. When arranging an abortion for Jean, he learns from the doctor that the last girl who he “got into trouble” almost three years ago didn’t go through with the procedure, and moved back home to Akron to have the kid instead. Later, driving back East to New York without so much as a gig for his trouble, Davis sees the lights of Akron pass in the distance, but doesn’t slow to stop. Davis even abandons the lone responsibility that he does take on—the care of a stray orange tabby cat that he adopts after mistaking it for the cat of one of his Upper West Side benefactors that had escaped through his negligence.

As in “Queen Jane”’s contrast with Davis’s fecklessness, the film’s musical breaks are packed with narrative information, the songs interfacing in uncomfortable and often adversarial ways with the world of the movie. When Davis watches others perform, he sees nothing but his own professional impasse, and the occasion becomes an excuse for him to vent, as when watching Troy Nelson (Stark Sands), a clean-cut Army brat moonlighting as a folk singer on leave from Fort Dix. “Wonderful performer,” says wide-eyed Jim, to which Davis responds, “Is he?” When Troy is joined on stage by Jean and Jim, they all harmonize on “500 Miles”—a tune popularized by Peter, Paul, and Mary—and as the room starts to sing along to the chorus, Davis looks around incredulously, as if to say, “You idiots like this?” The club owner, a pompadour-sporting Italian-American named Pappi (Max Casella), settles down next to Davis. “That Jean,” he confides, “I’d like to fuck her.” The Coens take great delight in such moments, which subvert the romantic sentiments expressed in these ballads with rude incursions of indelicate life. When Davis is paying a financially-motivated visit to his sister, she digs up a box of Davis’s old keepsakes, including a recording of Ewan MacColl’s “Shoals of Herring” made for his parents when he was “like eight years old.” Later, Davis will perform the same song for his infirm father, who now lives in an assisted living facility by the sea. Instead of applause or beaming pride, Dad responds to the performance by soiling his britches.

Isaac’s virtues and limitations as a performer are Davis’s: He’s a fair singer with a direct manner that conveys a frank inconsolability. The character’s limitations as a man are more glaring. Davis has the gall to try to borrow money from the friend he’s cuckolded, for the purposes of paying for the cuckolding accomplice’s abortion. While he forebears a great deal of scorn, the only public humiliations that Davis hands out in turn are directed towards two perfectly innocent middle-aged women, presumably because they make easy targets. (“This is my job! This is how I pay the fucking rent! I’m a fucking professional!” he yells at one of his benefactors, apparently oblivious of the irony.) When fresh-scrubbed and clear-eyed is the flavor of the day, the saturnine, dark Davis tends to favor more angsty material. Perhaps it’s an impulse catalyzed by his partner’s death; their signature tune, “Fare Thee Well (Dink’s Song)”, which recurs three times in the movie in three very different contexts, is fairly soaring stuff–while the line “Muddy river runs muddy and wild/ Can’t give a bloody for my unborn child” recalls Davis’s paternal reluctance. As a solo act, Davis is introduced singing the limping “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me,” a song in which the narrator describes himself as a “Poor boy.” (The tune was a Van Ronk standard.)

Davis may fancy himself a “poor boy,” but the movie that bears his name is worthwhile because it interrogates his self-pity rather than merely decorating it. We see inside Llewyn Davis, but also see the outside. “All the same shit is gonna keep happening to you,” Jean tells Davis, in a moment of rare insight, “because you want it to.” Having traveled from New York to Chicago and back to New York, Davis’s journey will literally end where it began. The film is bookended by the same scene—Davis singing “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me,” apologizing to Peppi, then stepping out into the alleyway behind the club where he has the snot kicked out of him by a big hombre who’s waiting there to avenge Davis’s needless, malicious heckling of his wife the previous night. Just as the housecat that Davis allowed to escape eventually makes its way home to the Upper West Side, so does he return as if by habit to his natural habitat: Defeat.

Davis may fancy himself a “poor boy,” but the movie that bears his name is worthwhile because it interrogates his self-pity rather than merely decorating it. We see inside Llewyn Davis, but also see the outside. “All the same shit is gonna keep happening to you,” Jean tells Davis, in a moment of rare insight, “because you want it to.” Having traveled from New York to Chicago and back to New York, Davis’s journey will literally end where it began. The film is bookended by the same scene—Davis singing “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me,” apologizing to Peppi, then stepping out into the alleyway behind the club where he has the snot kicked out of him by a big hombre who’s waiting there to avenge Davis’s needless, malicious heckling of his wife the previous night. Just as the housecat that Davis allowed to escape eventually makes its way home to the Upper West Side, so does he return as if by habit to his natural habitat: Defeat.

The second time this scene pops up, we also see Davis perform another piece of his repertoire—“Fare Thee Well”—all the way through for the first time, suggesting either that Davis has come to some new kind of acceptance of his partner’s death, or that he is bidding the stage itself goodbye. He puts the song over with the audience, and walks out as the next act is starting—a kid with curly hair and a nasal delivery singing a tune that begins “Oh it’s fare thee well my darling true…” The song is “Farewell,” and the kid is Bob Dylan. The-times-they-are-a-well, you know. There’s not a lot of money in songs about hanging and childbirth death in 1961, but if Davis doesn’t go off a bridge himself, he’ll encounter a zeitgeist that might be a better fit for his personality come the end of the decade. (This week I had the pleasure of seeing the filmmaker James Gray speak at the Marrakech International Film Festival, and he made a salient point: “If you look at Martin Scorsese’s career, or Joel and Ethan Coen, to name a couple of American filmmakers who are now commercially viable directors, the audience came to them.”)

For every Bob Dylan, how many dozens of Llewyn Davis’s were there, with albums languishing unsold on the shelves? For every Coen Brothers, how many has-beens and would-bes never got up the same “festival buzz”? I won’t say that the Coens have never experienced adversity before, for their track record is not one of continuous popular success, but at least they’ve always had one another, and so what they’ve managed with Llewyn Davis is a significant work of imaginative empathy, picturing not only the flipside of their good fortune and professional comportment, but what it might be like to be one half of a sundered duo.

“You’ve probably heard that one before,” Davis says shortly before he cedes the stage to Dylan, “Because it was never new and it never gets old and it’s a folk song.” This bit of routine banter gets at something essential to Llewyn Davis, a movie which touches on certain perennial emotional truths. As Davis’s wrenching performance of “Queen Jane” plucks up an unbroken thread running between 1537 and 1961, making them suddenly proximate, so Llewyn Davis is a period piece that takes no stock in the idea of the past as another country. You may never have set foot in the Cafe Reggio or the Gaslight Café or walked into Chicago from the outskirts on a slate-gray day, but after the credits roll, you feel like you’ve walked a mile in Davis’s soggy shoes. Maybe you even have.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound magazine and sundry other publications. He lives in Brooklyn, NY. Follow Nick on Twitter @NickPinkerton.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound magazine and sundry other publications. He lives in Brooklyn, NY. Follow Nick on Twitter @NickPinkerton.